Chiral Overview

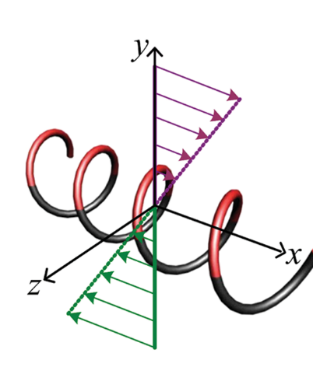

Chiral particles drift in shear flows because of their asymmetric shape. A simple case that helps to understand this drift is provided by Marcos et al. (PRL 2009) where a helical particle is aligned with a simple shear flow.

The segments perpendicular to the flow direction have greater resistance than those parallel to the flow. Since the top (red) and bottom (black) halves experience different external flow velocity in a shear flow, there is a net force acting perpendicularly to the axis of the helical particle. In the case shown in the schematic above, the net force on the particle results in a drift to -z direction.

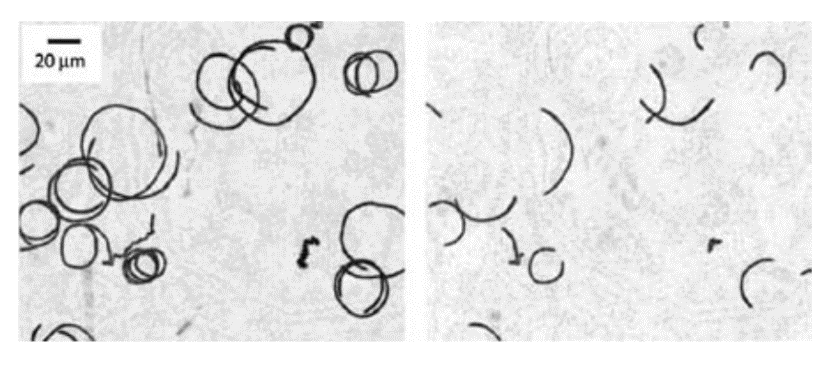

Lauga et al. (Biophysical Journal 2006) showed that bacteria (E. coli) near a wall swim circularly instead of straight because of the asymmetry in the flagella and the stronger viscous drag near walls. This motion could potentially break the symmetry of the flow and the resulting flow field can be complicated. An assumption here is that if the bacteria swim in an asymmetric way, the induced flow field will be asymmetric.

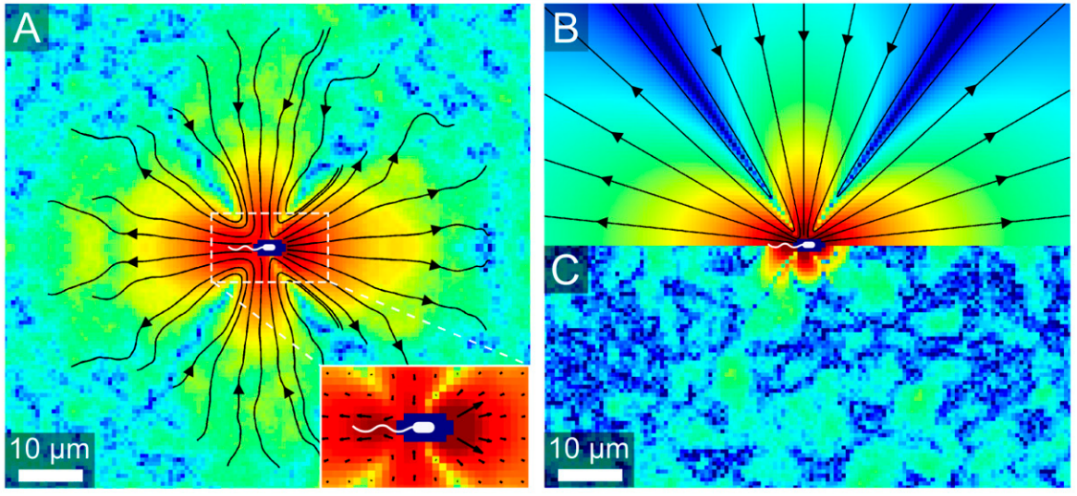

Drescher et al. (PNAS 2011) measured the far field flow field generated by swimming E. coli by tracking spherical tracers. Their results showed that the flow field could be well approximated by a flow induced by a force dipole. However, spherical tracers may have hindered the identification of the chirality in the flow.

Drescher et al. (PNAS 2011) measured the far field flow field generated by swimming E. coli by tracking spherical tracers. Their results showed that the flow field could be well approximated by a flow induced by a force dipole. However, spherical tracers may have hindered the identification of the chirality in the flow.

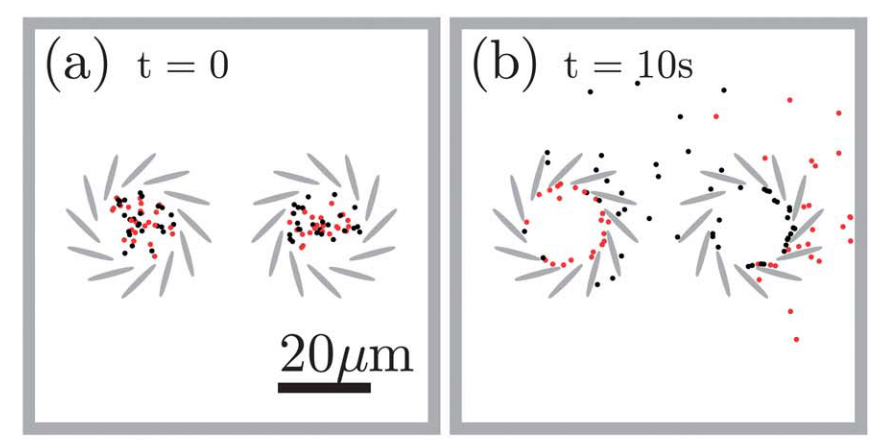

Mijalkov et al. (Soft Matter 2013) studied the separation of swimming enantiomers by simulation. They showed that static chiral patterns is capable of sorting enantiomers efficiently.

In order to investigate the chirality of the flow generated by swimming bacteria, and explore novel methods for enantiomer separation, we study the diffusion of synthetic (biological) chiral particles in swimming bacterial bath.